Dementia prevention is often described as a checklist—sleep more, eat better, exercise, manage stress. Those steps matter, but prevention becomes more effective when it is treated as a long-term system rather than a short-term goal. In geriatrics, wellness and prevention focus on protecting the brain through daily stability: maintaining cardiovascular health, reducing inflammation, sustaining cognitive reserve, and preventing avoidable injuries that accelerate decline.

This whole-person approach is increasingly emphasized in integrated care settings such as Liv Hospital, where brain health is evaluated in the wider context of physical function, chronic disease management, and quality of life.

What “Prevention” Really Means in Geriatric Dementia Care

Prevention is not one single action. It includes three layers:

- Primary prevention: reducing risk before symptoms appear

- Secondary prevention: detecting early cognitive changes and slowing progression

- Tertiary prevention: preventing complications and preserving independence after diagnosis

A useful way to think about dementia prevention is that it targets the “drivers” that influence brain aging—blood flow, metabolic health, sensory input, sleep quality, social engagement, and physical safety.

This layered viewpoint aligns with how GERIATRICS Dementia Wellness and Prevention is approached clinically, where daily habits and medical risk factors are treated as interconnected rather than separate topics.

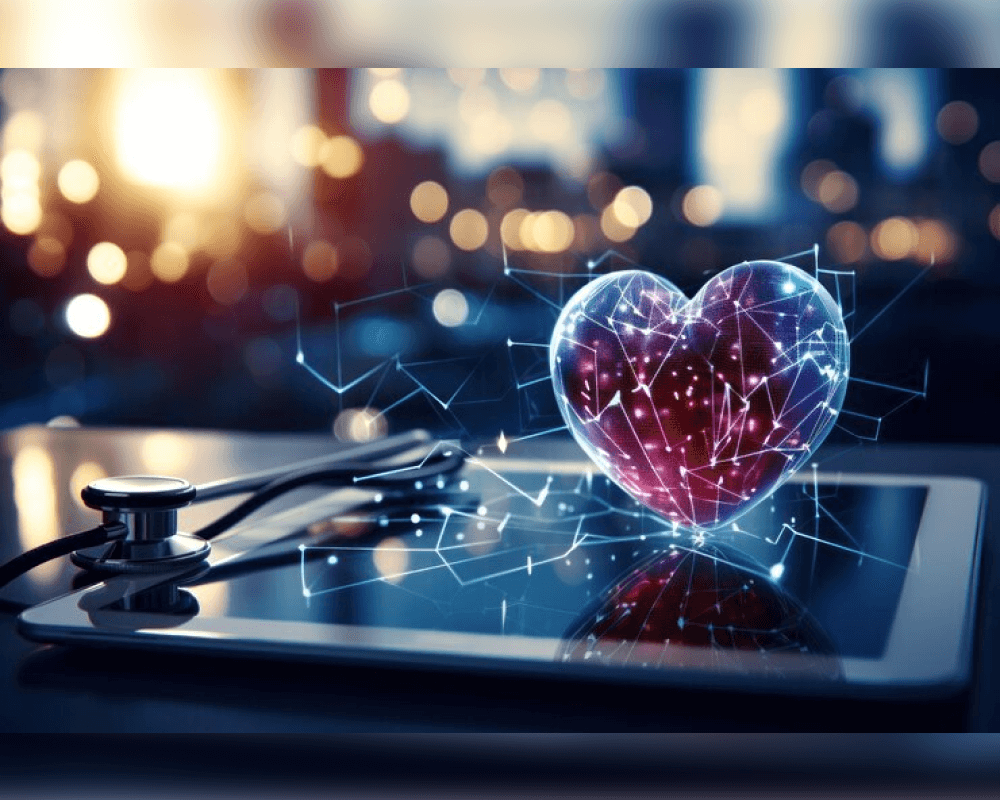

The Brain–Heart Link: Why Vascular Health Is a Prevention Strategy

The brain is an energy-intensive organ that depends on a constant supply of oxygen and nutrients. Many cognitive disorders are influenced by vascular factors—hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, and small vessel disease can quietly damage the brain over time.

A prevention-focused geriatric plan typically prioritizes:

- blood pressure control

- blood sugar stability

- lipid management

- regular movement to support circulation

- reducing sedentary time

These steps matter because “what protects the heart often protects the brain,” especially in older adults.

Cognitive Reserve: Building a Buffer Against Decline

Cognitive reserve refers to the brain’s ability to compensate for age-related changes and maintain function. It isn’t about being “smart”; it’s about strengthening networks through consistent mental engagement across life.

Activities that support cognitive reserve include:

- learning something new (language basics, music, a skill-based hobby)

- reading and summarizing content (active reading, not passive scrolling)

- strategy games that require planning

- group-based activities that combine social + cognitive effort

- tasks that require sequencing and attention (cooking, gardening, DIY projects)

The key is novelty and consistency. Repeating only what is easy doesn’t challenge the brain enough to strengthen adaptability.

Sleep as “Night Maintenance” for the Brain

Sleep is not only rest; it supports the brain’s housekeeping and repair processes. Poor sleep can intensify memory issues, increase daytime confusion, and reduce emotional stability—factors that can imitate or worsen cognitive decline.

Prevention-oriented sleep habits in older adults often focus on:

- consistent sleep and wake times

- light exposure in the morning to support circadian rhythm

- limiting late-day caffeine and heavy meals

- reducing nighttime fall risk with safe lighting

- addressing snoring or breathing pauses that may suggest sleep apnea

Sleep quality is especially important because it influences mood, energy, attention, and memory—four areas commonly affected early in cognitive decline.

Sensory Health: Vision and Hearing as Brain Protection

Hearing and vision loss are not just “inconveniences” in geriatrics—they can reduce brain stimulation and increase isolation, which may worsen cognitive outcomes. When someone struggles to hear conversations, they often withdraw socially and mentally, meaning the brain receives less input and fewer challenges.

Wellness-focused prevention includes:

- hearing checks and timely hearing aid support when needed

- regular eye examinations and management of treatable vision issues

- optimizing lighting at home to reduce strain and falls

- minimizing background noise in social environments to improve communication

Maintaining sensory input helps keep the brain engaged with the world, which is one of the simplest but most underestimated prevention strategies.

Fall Prevention: A Direct Way to Reduce Dementia Risk

Head injuries can increase the risk of cognitive decline, and falls are one of the most common sources of traumatic brain injury in older adults. Even when a fall doesn’t cause a major concussion, it can trigger fear, reduce mobility, and increase dependency—each of which accelerates decline.

Practical fall-prevention steps include:

- strength and balance work (walking, chair exercises, tai chi, resistance training)

- home safety adjustments (remove loose rugs, improve lighting, install grab rails)

- medication review for dizziness and blood pressure drops

- supportive footwear and mobility aids when appropriate

Prevention becomes far more realistic when the environment is designed to support stability.

Social Connection: A Brain Health Behavior, Not a Personality Trait

Loneliness and chronic stress affect inflammation, sleep, and motivation, all of which shape cognitive health. Social connection protects the brain partly because it combines emotional regulation, language processing, memory, and attention in one activity.

Effective approaches include:

- structured weekly social routines (not “maybe we’ll meet”)

- joining groups that create recurring contact

- volunteering with a consistent schedule

- connecting around shared tasks rather than only conversation

The goal isn’t constant socializing; it’s meaningful, recurring engagement that keeps the brain active.

Prevention That Matches Real Life

The most successful wellness plans are sustainable. Instead of changing everything at once, prevention strategies work best when they are built into normal routines—walking after meals, preparing simple Mediterranean-style meals, staying consistent with health checks, and protecting sleep.

If you want a lifestyle-based approach to building sustainable routines for long-term well-being, the final piece of the puzzle often comes from platforms like live and feel, where healthy habits are framed as everyday systems rather than one-time resolutions.